AI-based watchdog for mobile networks

The digital world without 5G is inconceivable. The technology plays a crucial role not only for mobile communication in our private lives but also for industry: today, many companies use 5G networks to steer time-critical processes. Car manufacturers, for example, control the complex interaction of assembly robots on the factory floor via mobile communication. The problem here is that it is very simple to paralyse or spy on 5G networks. To prevent this, Stefan Valentin, Professor of Mobile Networks at h_da’s Faculty of Computer Science, and his team have developed an AI-based protective shield, a “watchdog” called NERO (Network Real-time Observer), see impact 19.11.23. The project, in which partners from science and industry are participating, is now nearing its successful completion after two years of funding from Germany’s Federal Office for Information Security (BSI): NERO can be relied on to raise the alarm in an emergency and is now being further developed for broad application in practice.

Interview: Christina Janssen, 11.2.2025

impact: How is NERO?

Professor Stefan Valentin: NERO is fine. He is lying in wait and doing his job as a reliable watchdog.

impact: Is NERO still alone or does he already have some conspecifics?

Valentin: NERO is already in operation in various places and has been copied several times because he is – and this is part of his charm – “only” software. This gives him the great advantage that he can be easily adapted to new situations.

impact: Where is NERO already in operation?

Valentin: On the one hand, here at h_da, but also in a partner project at the University of Duisburg-Essen, which was about steering trucks as they approach the loading ramp. The intention was for this to be done automatically over the last few metres and controlled via a 5G network. We tested whether NERO could protect this network – and he proved his worth.

impact: If the network were to be disrupted during such a process, the docking process would not work properly and, in the worst-case scenario, the truck would crash into the ramp...? How can NERO prevent this?

Valentin: We can rely on NERO to raise the alarm as soon as he detects a suspicious radio signal. He can distinguish such anomalies from normal radio waves. An analogy would be a public building, for example, where lots of people constantly go in and out. Here, NERO has to differentiate between who is allowed in and who is not.

impact: How did NERO learn to differentiate?

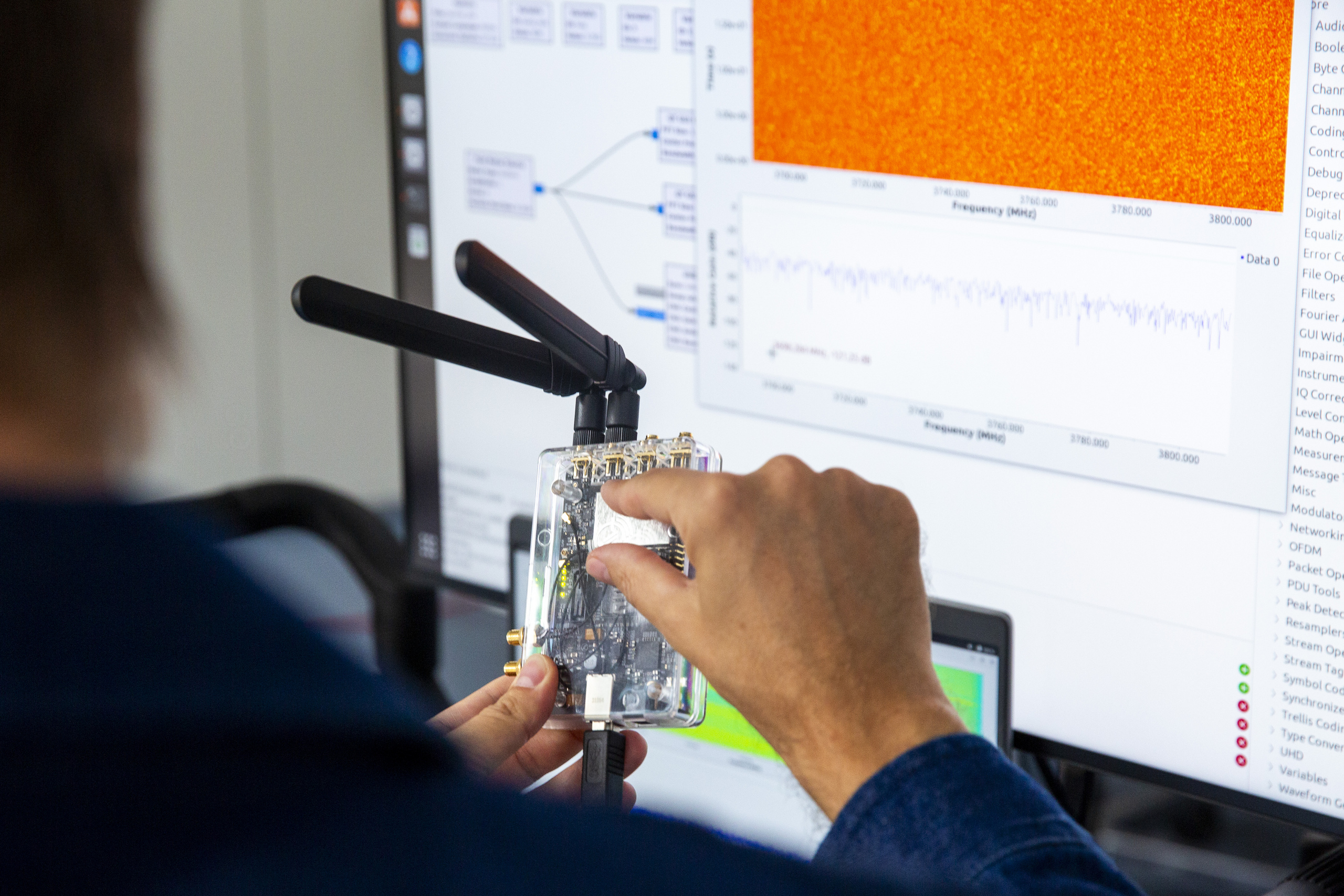

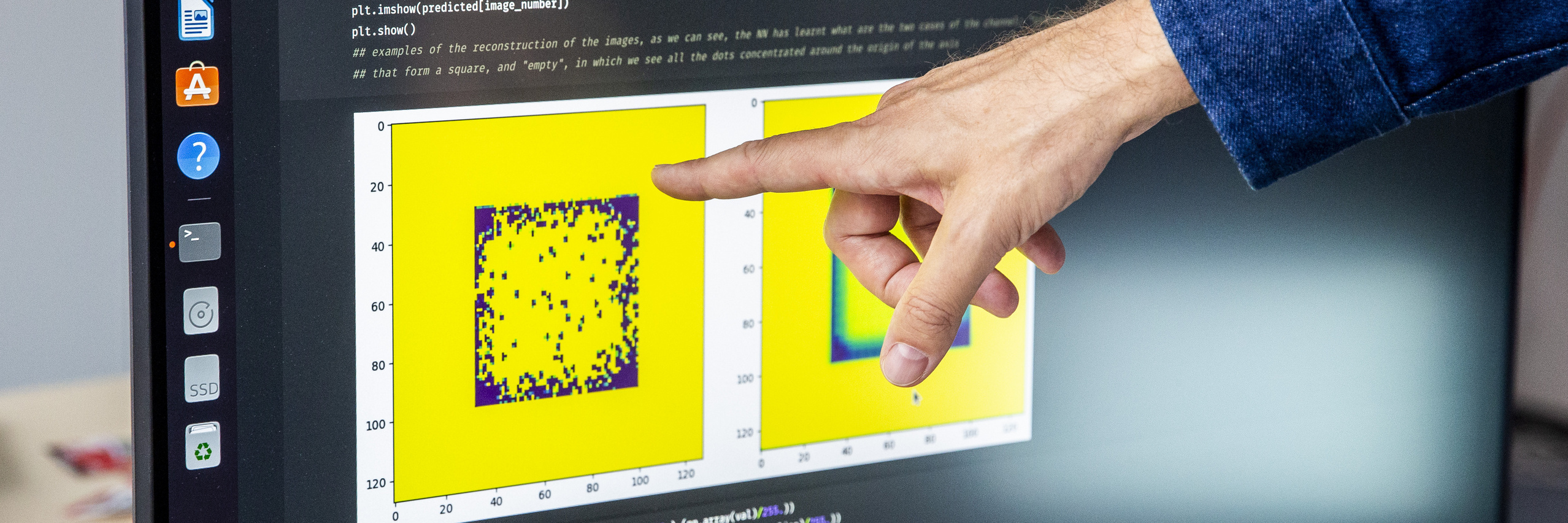

Valentin: We use machine learning, a subdomain of artificial intelligence. The watchdog is pre-trained with partly “real” and partly synthetic signals, then he assesses the situation, makes further progress under our supervision and then we “let him off the leash”. After that, he has to manage on his own.

impact: Does NERO continue to learn while he is working?

Valentin: If we allow him to, then yes. However, the difficulty is that you have to prevent NERO from being “poisoned” while he is working.

impact: How is that possible?

Valentin: By an attacker deliberately generating false signals to manipulate the model. This would lead to false alarms or attacks being overlooked. This can also be done by slightly tweaking the input data in order to take advantage of the AI model’s characteristics. This is known as adversarial machine learning.

impact: In our last interview, we talked about “sneakers” and “stilettos”, that is, attacks that are rather crude and therefore easy to detect, and attacks that are technically sophisticated. Does NERO recognise both?

Valentin: Yes, indeed, whereby we have established that “stiletto” attacks, which focus on specific frequencies, are the main problem with 5G. This is one of the key findings from the project: it is extremely easy to disrupt 5G in this way because – in my opinion – nobody thought about this aspect during standardisation. The aim of NERO is to protect against this vulnerability.

impact: What kind of vulnerability is it?

Valentin: The problem was first demonstrated by a Norwegian research team in 2022. The vulnerable 5G signal is called SSB, which stands for Synchronisation Signal Block. To be able to connect to a mobile phone mast, all cell phones must receive this signal. Although it is so critical for the functioning of the mobile network, it only covers 3 to 6% of the total bandwidth. This means that the attacker only needs to disrupt a small part of the 5G spectrum – coming back to “stilettos” – to paralyse the wireless network in a specific area. This can be done with hardware that costs around €100. If I wanted to disrupt the entire bandwidth, I would need hardware that costs around €15,000, meaning that this cost-benefit ratio is very bad for existing networks and very good for attackers.

impact: Does this mean that we ought to change the standardisation or “approval” process for new mobile technologies in the future?

Valentin: I have put forward some suggestions for this in the NERO project. For example, you can take inspiration from the coexistence of Bluetooth and WiFi signals. This is possible with “frequency hopping” and extremely robust. This could be implemented accordingly for 6G.

An AI Watchdog to Protect 5G Mobile Networks from Smart Jammers

impact: When will 6G arrive?

Valentin: 6G is now progressing from the research stage to standardisation. We are expecting first real-world deployments in about 2030. This is the normal evolutionary process in which, roughly speaking, a new generation of mobile networks comes along every 10 years.

impact: Does that mean the end for NERO?

Valentin: We cannot be sure that my suggestions for standardisation will be accepted. This is a global issue that is also complicated from a political perspective. If yes, the stiletto problem would be solved. Nevertheless, NERO would not be obsolete because normal broadband jamming and other attacks would still be possible.

impact: Your research is therefore intended not only to protect the existing 5G standard but also to make future standards more secure.

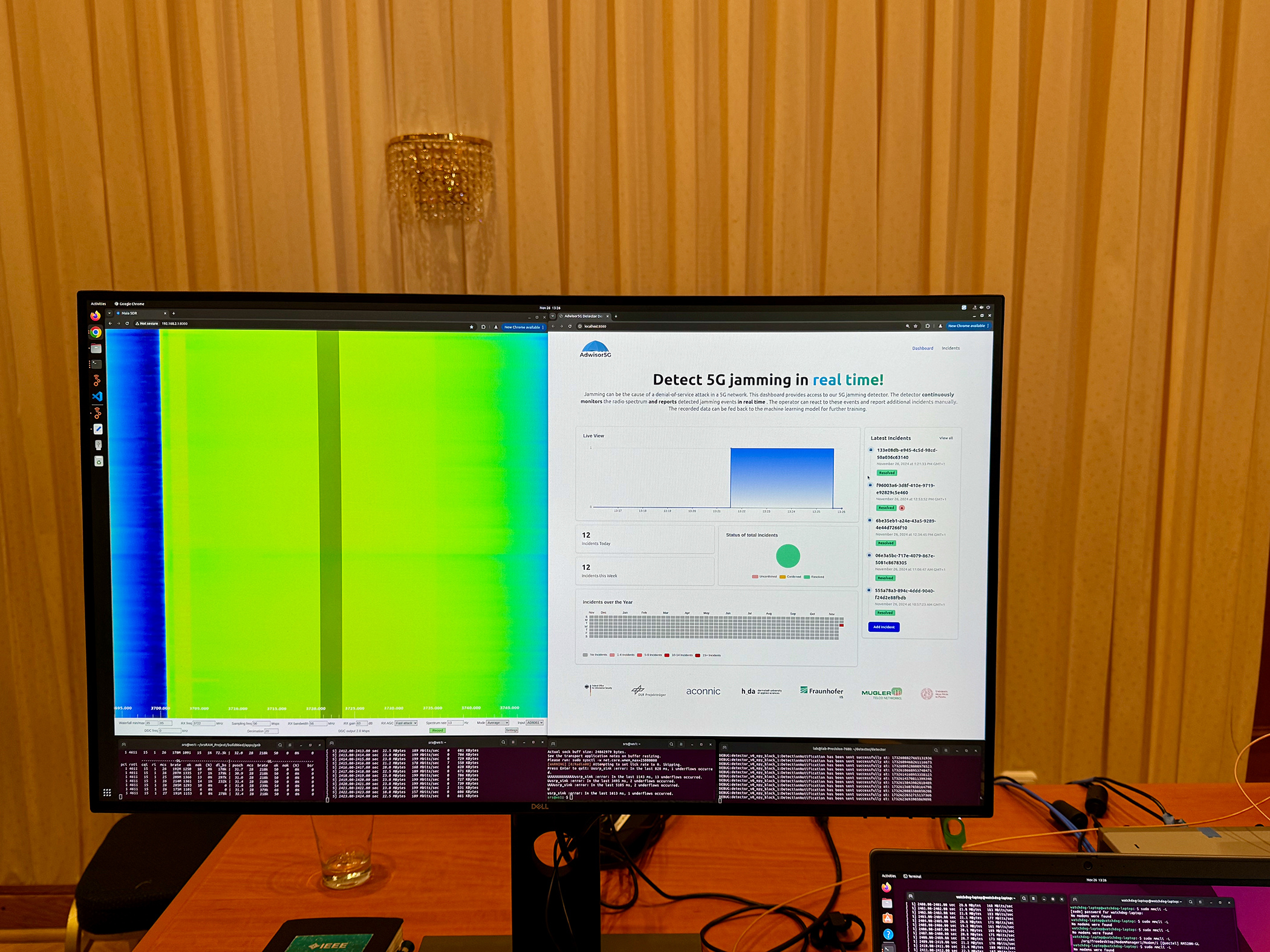

Valentin: To make them more secure and extend them. The good thing is that our NERO watchdog works independently of the standard for all networks. He recognises suspicious patterns in signals in real time, triggers an alarm and tracks these patterns, also in real time – so he stays on the trail once he has apprehended the “intruder”. This makes it easy to locate the jammer. The great thing is that jammers are only effective when they are physically active, so they cannot hide completely.

impact: When and where will NERO go into operation in practice for the first time?

Valentin: I am currently discussing with EFE GmbH in Ober-Ramstadt how we can launch NERO on the market. But before we can do that, NERO still has a lot of new situations to “learn”. He can already handle level ground and indoor spaces very well, and he can manage a university campus quite well, too. But there are situations for which NERO is not yet trained. For example, busy squares in inner cities. The second point is hardware design: the ultimate goal is to attach NERO to mobile phone masts as a “watchdog”, which means that he needs to be weatherproof, for example. We have in mind a self-sufficient system that is not integrated into the base station and thus manufacturer-independent.

impact: Why is self-sufficiency so important for NERO?

Valentin: The watchdog should not lie comfortably under the bed inside the house but instead sit outside it so that he himself is not caught unaware. Around 80 percent of mobile phone masts in Germany run on Chinese technology. Many now find this dodgy, but we cannot turn the clock back overnight. If we position a watchdog next to these masts that is completely separate from the suspicious hardware, we have a reliable alarm system for the network’s self-protection. In this way, our research might also strengthen trust in our networks overall.

Publications

M. Varotto, F. Heinrichs, T. Schürg, S. Tomasin and S. Valentin, „Detecting 5G Narrowband Jammers with CNN, k-nearest Neighbors, and Support Vector Machines,“ in Proc. WIFS, Dec. 2024.

ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/10810672

M. Varotto, S. Valentin, F. Ardizzon, S. Marzotto, and S. Tomasin, „One-class classification and the GLRT for jamming detection in 5G private networks,“ in Proc. SPAWC, Sep. 2024, invited paper. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/10694335

M. Varotto, S. Valentin and S. Tomasin, „Detecting 5G Signal Jammers Using Spectrograms with Supervised and Unsupervised Learning,“ in Proc. ICC WS, Jun. 2024. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/10615325

S. Rieger, L.-N. Lux, J. Schmitt, M. Stiemerling, „DigSiNet: Using Multiple Digital Twins to Provide Rhythmic Network Consistency,“ in Proc. NOMS WS, Mai 2024.

https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/10575632

M. Varotto, S. Valentin and S. Tomasin, „Detecting 5G Signal Jammers with Autoencoders Based on Loose Observations,“ in Proc. GLOBECOM WS, Dec. 2023.

ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/10464951

A. Birutis und A. Mykkeltveit, „Practical Jamming of a Commercial 5G Radio System at 3.6 GHz“, in Proc. ICMCIS, Jan. 2022.

doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2022.09.007

Contact h_da scientific editorial team

Christina Janssen

Science Editor

University Communications

Tel.: +49.6151.533-60112

Email: christina.janssen@h-da.de

Translation: Sharon Oranski

Studying computer science at h_da

Links