“This is shaking up the whole construction industry.”

![[Translate to Englisch:] Deponie mit alten, ausgebauten Fensterrahmen](/fileadmin/Bilder/Forschung/22_06_07__Fensterrahmen.jpg)

In view of climate change and finite resources, some radical rethinking is necessary in architecture and the construction industry too. Urban mining is one of the concepts pointing in the right direction. The idea: buildings are planned and constructed from the outset in such a way that – as far as possible – all the individual components, from the shower tray to the roof tiles, can be used again in an appropriate way. In this interview for impact, architecture professor Marcin Orawiec and contract lecturer Jasmina Herrmann from h_da explain what exactly is understood by this and what is still standing in the way.

An interview by Christina Janssen, 27.6.2022

Professor Orawiec, most people are by now probably familiar with the term “urban gardening”. But what is “urban mining”?

Marcin Orawiec: In essence, urban mining is concerned with the question: How should we be handling our natural resources? It’s about establishing a real circular economy, reusing construction materials from demolished buildings and stopping the depletion of our natural environment.

impact: In urban mining, cities and towns replace nature as a source of raw materials, is that right?

Jasmina Herrmann: Yes, you could put it like that. In principle, it means that we humans have built up a huge “materials deposit” in the habitat we’ve created ourselves, the anthroposphere. This deposit is growing all the time: we’re continuing to use the raw materials we’ve extracted from the earth to make cars, buildings and infrastructures. The deposit is becoming too big and structures no longer in use are dumped back into nature. Landfills in the Rhine-Main region, for example, are meanwhile almost full, and we’ve reached a point where nature can no longer regenerate the used raw materials. That’s why we must stop taking raw materials from nature and instead help ourselves to what “our deposit” has in stock. There is now even talk of the “Anthropocene”, the age of humankind.

impact: Professor Orawiec, you’ve been teaching architecture at h_da for 28 years and have an office in Aachen, OX2architekten, together with your wife. Ms Herrmann, you completed your master’s degree in architecture at h_da two and a half years ago and are now working as a contract lecturer. Why is the topic of urban mining so important to both of you?

Herrmann: I’m very interested in future-oriented topics. My aspiration is to promote these topics at our university and in our society and inspire students for them.

Orawiec: In view of population growth and the global economy, it has to be said that we’ve in fact come to the end of the road as far as resource consumption is concerned. This is an issue in all sectors of the economy. For us, this means: we must educate our students in such a way that they can react to this appropriately and contribute to more sustainability. That’s why we anchored the topic of urban mining as a special focus in the curriculum a few years ago.

impact: What does that mean in concrete terms for construction and architecture?

Orawiec: The construction industry urgently needs to start thinking about new production processes. It’s no longer about recycling, that’s the thinking of the last 20 years, where we used an enormous amount of energy to incinerate or separate things or process them in other ways, purportedly to produce something new from old material. That was a dead end. Urban mining means taking things from stock that can be further processed without vast energy expenditure.

impact: Is that always possible?

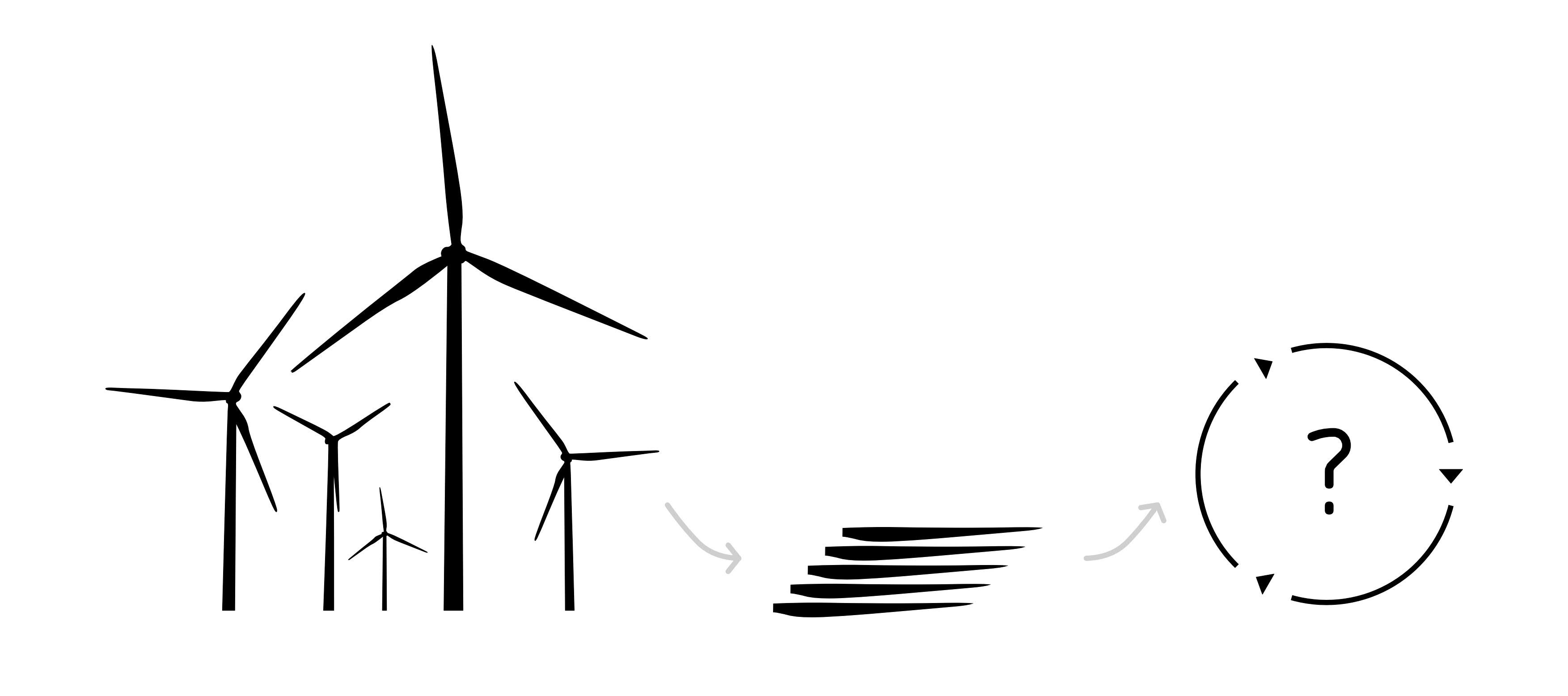

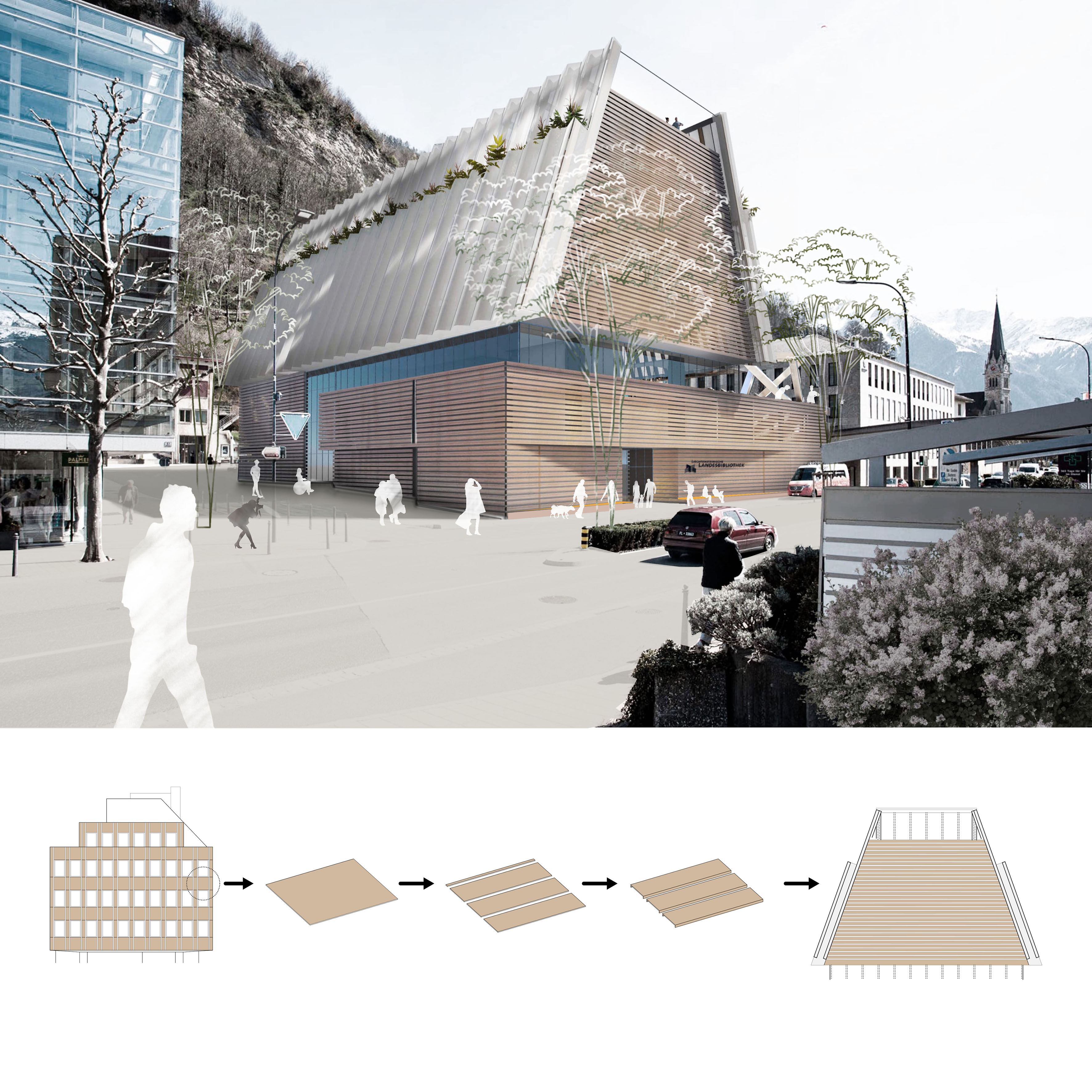

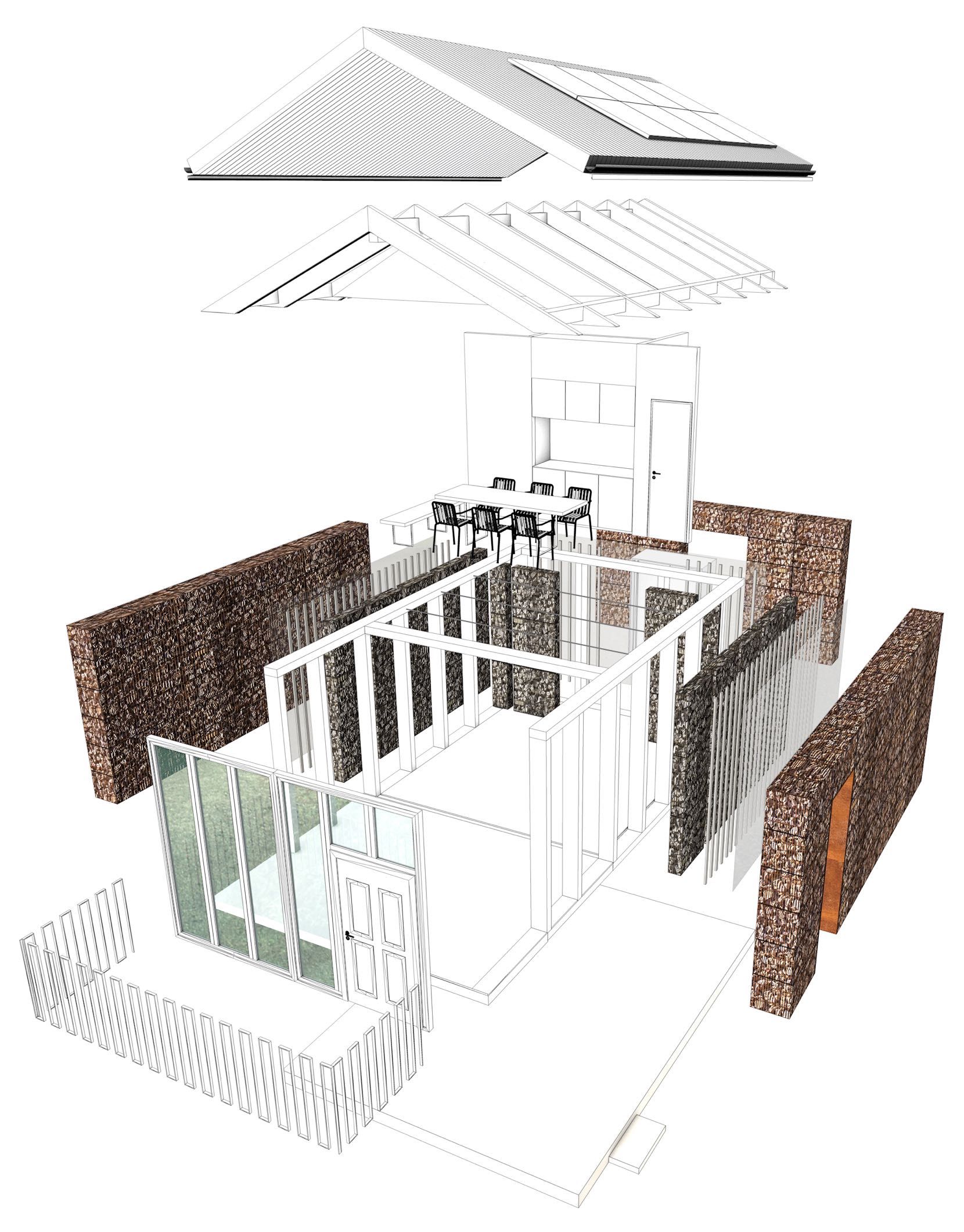

Orawiec: Not yet. That’s why the most important thing is to plan and build today in such a way that we can disassemble buildings into separate parts again after ten or twenty years. New buildings are then planned and built from these individual components. Cradle to cradle is what we call this cycle, where planning process, design, construction and life cycle are fundamentally rethought and the maxim of “circular thinking” applies. We started teaching this topic at the beginning of 2021, and shortly afterwards colleagues from civil engineering, environmental engineering and plastics technology contacted us to express their interest in working together. This is how we came up with a very unusual topic: the utilisation of scrap rotor blades from wind turbines. We offered a first course on this last semester, and our students submitted some great designs. We’re now continuing to work on this topic as an interdisciplinary group at h_da.

impact: Whether window handle or rotor blade – everything that was once installed ought to be used again. This is presumably more complicated than it sounds...

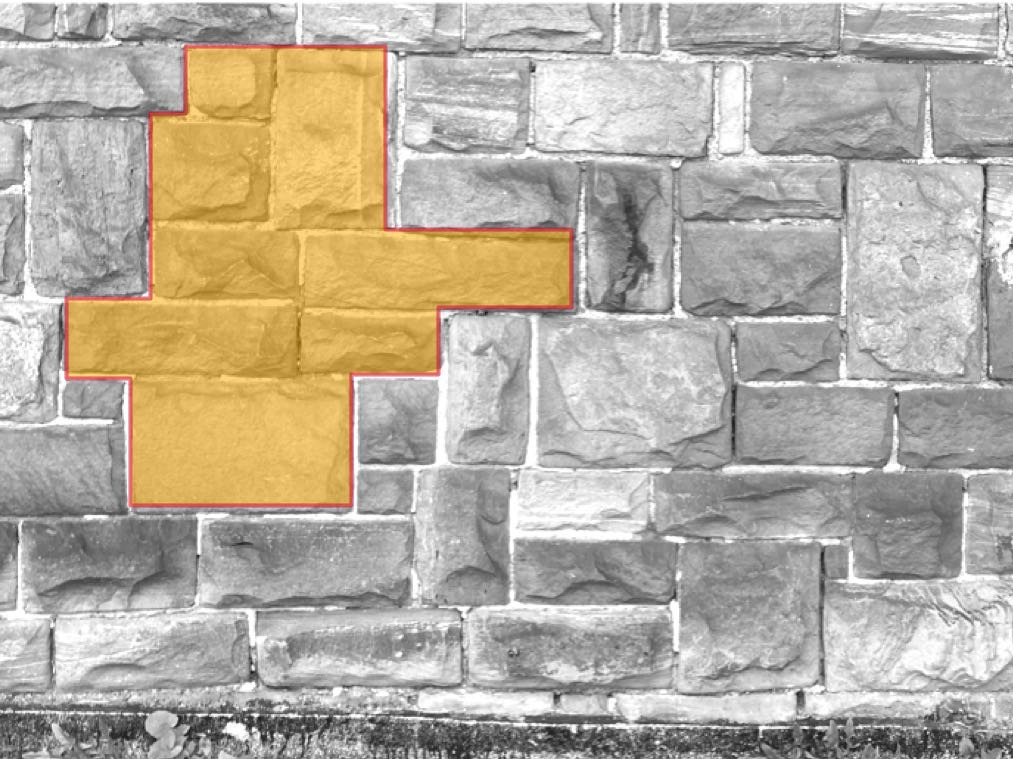

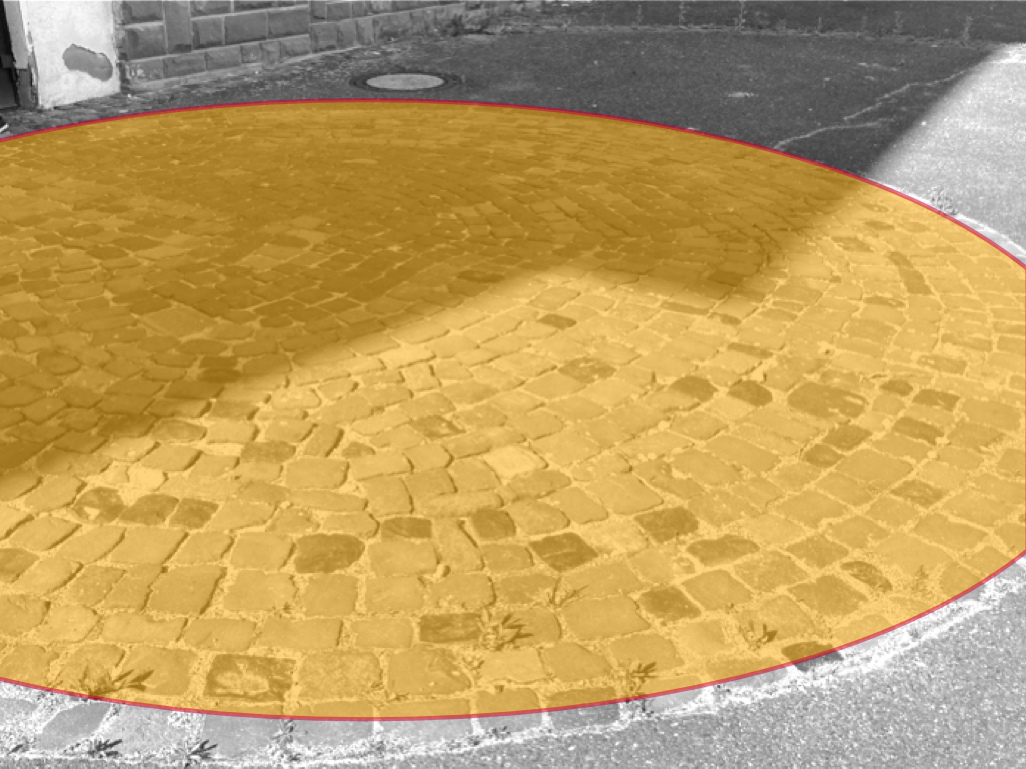

Herrmann: Basically, this topic is shaking up the whole construction industry. Today, there are strict phases that a construction process must pass through: we start with basic evaluation, preliminary planning, design planning. Then at some point the building application is submitted, and so on. Instead, what we should now be saying is: Let’s look around in the region first to see what building materials are available at the moment and where. Then we see that there are five buildings which are being demolished. We then collect the materials from them and compile an inventory: What roof tiles have we got, how many windows are there, what size are they? We can then use what we have at our disposal to design something new, but are dependent on the existing dimensions and materials. That’s the theory. But, in reality, it’s like this: the existing building has to go, and where can we store all the building materials temporarily until the sluggish authorities have checked everything and the tedious planning and contracting process is finished? How do we know where something is being demolished? Are materials perhaps contaminated? We need to compile cadastres. In other words, registers that show how much material has been used where and when it is likely to be available again. And we need large storage facilities from which we can call off materials. In addition, a legal framework must be created that provides a basis for planning and implementation.

impact: That’s not entirely new. Even today, bricks or concrete blocks, for example, are shredded and used again after a building has been demolished.

Herrmann: It’s generally a good thing if material does not end up in landfill. In this way, however, it’s downcycled: it can’t be reused on the same scale and for the same purpose. Our aspiration is, of course, to design buildings and other structures where the materials can be reused on a similar or the same level. The dictum is – as far as possible – not to glue but to screw or clamp materials together. A concrete example: Stuff the gap between the window frame and the wall, like was done in the past, instead of using foam. Then you can remove them again without damaging them and neatly separate all the components. Of course, this doesn’t work with everything. If you want a roof to be watertight, then you will have to make it watertight and glue or weld the membrane. It’s a balancing act. In principle, however, we need to fundamentally rethink all construction methods.

Orawiec: And the way to do it is via incentives – for example starting with the manufacturer who brings the products onto the market. Today, everything is done according to the principle of “Let the devil take the hindmost”. Sell the window, give a five-year guarantee, and nothing else interests us. Instead, there should be a kind of end-of-life product guarantee: politics should oblige manufacturers to take back their windows, bricks or steel beams after 20 years, refurbish them and put them on the market again with a new guarantee. And this should be combined with cataloguing. There is, for example, the “Madaster” initiative, a digital cadastre for materials that are systematically recorded and redistributed. This has meanwhile grown into quite a big organisation. These two pillars – incentives and cadastre – have to go hand in hand. The third pillar is building material dealers. They are already gearing up for the new business model. They will find places and ways to facilitate temporary storage.

impact: How realistic do you think it is that all this will be put into practice some day?

Orawiec: I’m very optimistic that we as a society, also as a society, will bring about these processes. And it’s all the more important that young people now entering these professions are prepared for them at university.

Herrmann: However, no single discipline can achieve all this by itself; it requires the interaction of a large number of experts. That’s why we at Darmstadt University of Applied Sciences are addressing the topic in cooperation with several very different disciplines.

Contact details

Christina Janssen

Scientific editor

Press department

Tel.: +49.6151.16-30112

E-Mail: christina.janssen@h-da.de

Translation: Sharon Oranski