To bee or not to bee

It’s a matter of life and death. In Professor Marcus Zinn’s BeeLab at h_da’s Faculty of Computer Science, the bees’ job is not only to collect honey: sensors record data on their communication behaviour – and much more besides. The scientist uses artificial intelligence to process these data and pool them on an open research platform. Unexpectedly, however, a species of Asian hornet that hunts – and eats – honeybees on a large scale is torpedoing the project. Killers and victims – research has its own thriller.

By Alexandra Welsch, 9.9.2025

A hive of activity has recently developed behind the building that is home to the Faculty of Computer Science. Towards the adjacent parkland stand four beehives in the peace and tranquillity between the bushes and trees. “Buzz, buzz, buzz,” hum the bees, as they swarm in and out of the holes in their wooden boxes. “Caution – Bees”, advise yellow signs – a warning that seems almost out of place in view of the pastoral scenery. But, as it soon becomes clear, hornets are (f)lying in wait...

“There’s one,” Professor Marcus Zinn calls out, pointing towards the unfamiliar flying object. It wafts past and hovers like a drone in the air above one of the entrances to the beehives. “That’s an Asian hornet,” he says. And it’s aiming straight for the bees. The next moment, it snatches one as it flies out of the hive. “For them, it’s like flying through McDrive,” says Professor Sinn dryly. “They devour a bee every few minutes.”

“I can’t say whether the bees will survive the winter”

When Zinn set up the bees’ little residence behind the faculty building with four young colonies of 10,000 bees per hive in May, shortly after taking up his professorship in software engineering at h_da, his intention was different. The original aim of the BeeLab is to encourage research on these insects in their role as honey experts and provide an open platform for projects in all disciplines, whether as a testing ground for AI applications or sensor test units, for sustainability assessments or biological studies. Now, however, the focus has unexpectedly shifted to examining what the advance of an invasive species of hornet means for the native honeybee, which is high up on the predator’s menu. And the more bees they kill, the fewer there are to bring food back to the hive – which in the long run can decimate entire colonies. That is why Zinn is already feeding them artificially with sugar. But it does not bode well: “I can’t say whether the bees will survive the winter.”

Zinn, 47, hails from Rodgau and first became interested in beekeeping around ten years ago, initially as a hobby. “I like trying out new things,” he says, his honey-blond hair falling in long waves onto his shoulders. He took a beekeeping course, got hooked and became an instructor himself. But he also sees a lot of potential in the exciting world of bees as an expert in software development and artificial intelligence. They can supply not only honey but also a whole lot of data. “As a computer scientist, it’s always better to have real-life applications,” he adds. In his opinion, this makes science more tangible – especially for students and schoolchildren, who are the bee project’s main target audience.

Behind the computer science building, he climbs into a white overall, dons his beekeeper’s hat with its face net and grabs the smoker. He looks a bit like a Ghostbuster as he approaches the beehives. He steps up to a box and blows smoke into the entrance hole. When he opens the lid, the little creatures swarm gently around him. He carefully pulls out a wooden frame and holds it up to the sunlight, the honey glistening golden from the combs, bees crawling and buzzing around. The killer hornets, by contrast, seem to be taking a short break, and all remains peaceful – for the time being.

Exciting application for computer science

“How can we assess whether the city is a suitable environment for bees?” asks Marcus Zinn, outlining the project’s overarching question. He adds: “This includes their enemies, of course, the hornets.” How do the bees react when the killers appear? He can report some first exciting observations: the guard bees, which are normally stationed at the front by the entrance hole, have retreated a little deeper into the hive. And their fellow bees now fly straight in without landing on the edge of the hole. “We need to study this behaviour in greater depth,” he says, “and this would be a good opportunity to do so.”

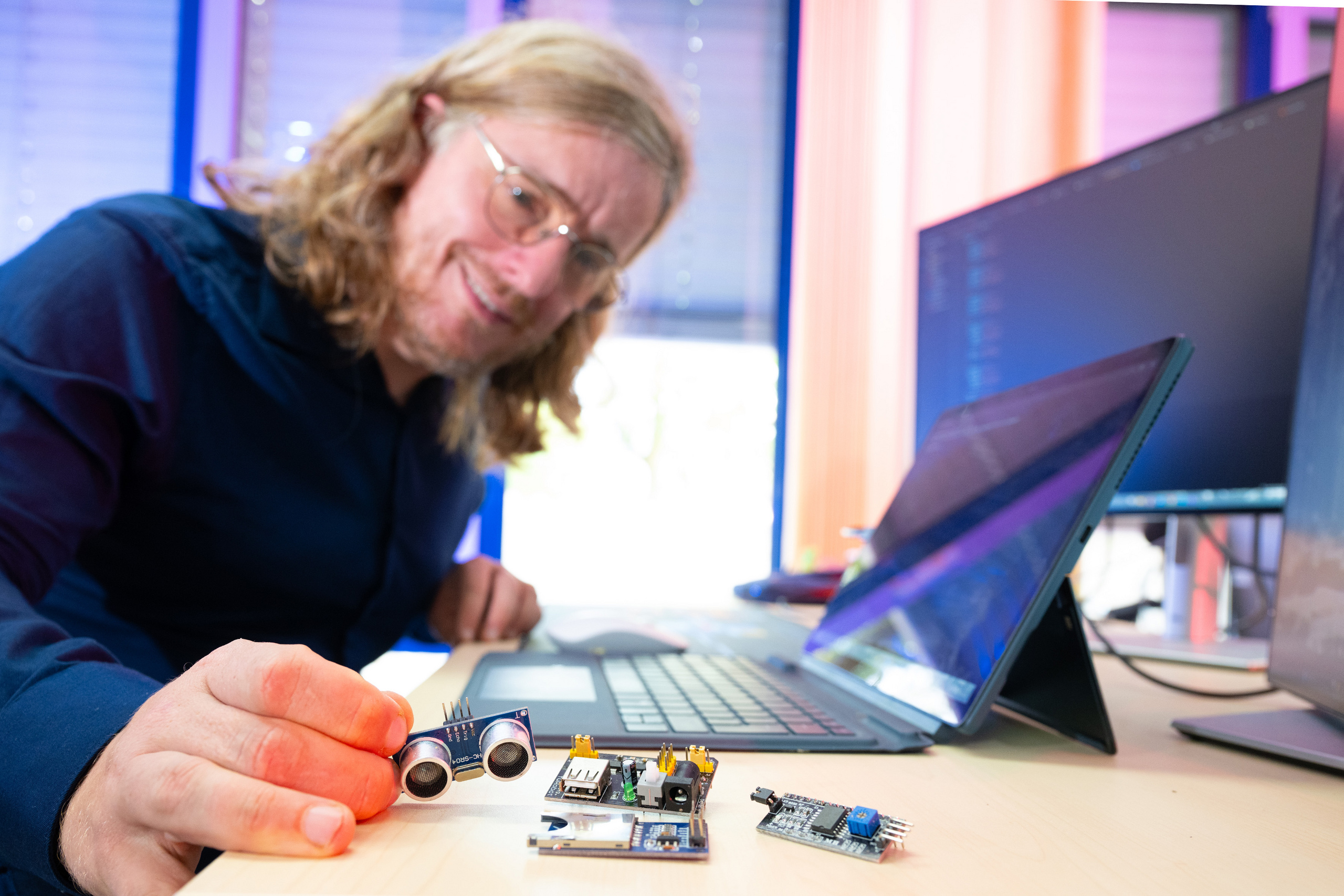

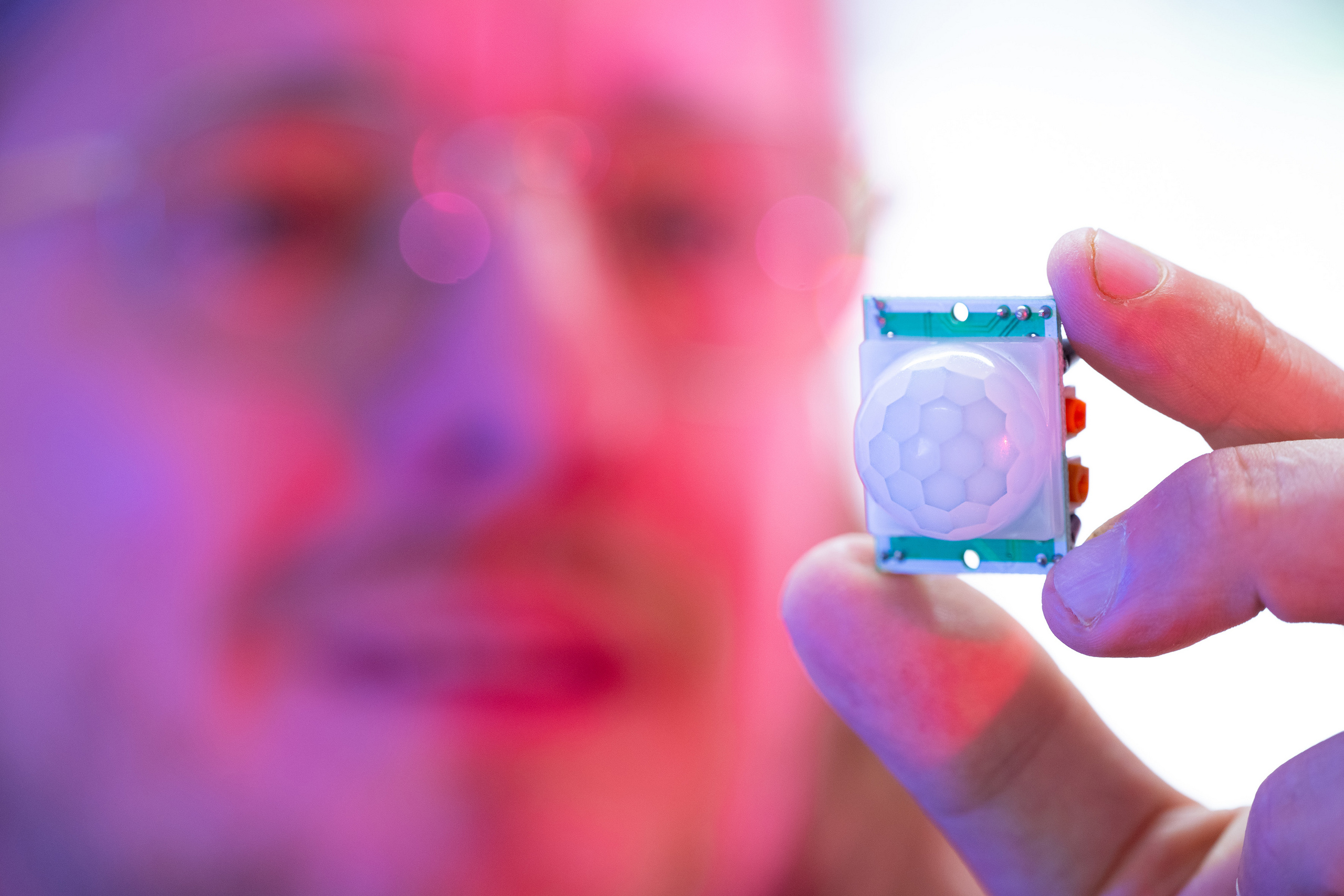

Step-by-step, sensors and cameras will be installed in the hives. Vibration sensors will measure how the bees communicate with each other: “Because they communicate via vibration.” Distance sensors will map the bees’ movements, and the temperature inside will also be measured continuously. In addition, cameras and microphones will produce sound and video recordings of life in the hive. External weather data will also be added. “Starting in the spring of next year, we want to use sensors to record everything,” announces Zinn, “then things will start to get exciting.” The data will be made available in real time in an open pool and can then be further processed and analysed with the help of AI.

That he is eagerly anticipating this next step is plain to see: “Other faculties have shown a lot of interest and support.” Several concrete projects starting in the winter semester are linked to the BeeLab. For example, Darmstadt Business School is planning a course dedicated to designing a digital twin, in which a digital copy will be modelled in a cloud on the basis of the bee data. The Faculty of Social Sciences is interested in a “bee-human study” that looks at questions of ethics, socioeconomics and biodiversity. And at the Faculty of Computer Science itself, a Master’s project in system development is dealing with sensor technology for bees and pollinator monitoring for plants, among other topics.

Making AI experienceable with real bee data

The bees are clearly popular! Marcus Zinn is delighted that five students already approached him on their own initiative during the start-up phase. A materials science student, for example, wants to build supports for attaching the sensors to the beehives in such a way that they disturb the bees as little as possible. To obtain a three-dimensional picture of communication dynamics in the hive, a fellow student plans to attach vibration sensors to each individual frame. “I believe this will give the students more experience,” says Professor Zinn. As the father of three children, he wants the project to reach out to youngsters too. “Our aim is for schoolchildren to experience and understand artificial intelligence in a practice-oriented and low-threshold way via the real bee data from the open web platform.” To this end, he wants to initiate partnerships with schools and industry.

All this is only possible, however, if the bees are not completely wiped out and able to deliver data. That is why it is now necessary to take the hornets into account all the time. As a stopgap, Zinn has mounted makeshift lattices in front of the beehive entrances to keep the killers away. Because some of them manage to slip through but then cannot find their way back out again, several have already died inside the hives. But wouldn’t spraying water be a more effective way to repel them, since – unlike bees – they don’t like water?

“We want to gather data and findings first,” says Zinn. If necessary, strategies can then be developed on this basis. But if the Asian hornets continue to go on the rampage, he will have to adopt other countermeasures first. “I’ll probably have to buy more bees to replace the ones we lose,” he fears. “As a computer scientist and beekeeping enthusiast, I would hate to abandon the project.” All the more so since it’s already delivering some sweet results: small jars of BeeLab honey are now in circulation – produced by the “humming members of the computer science team”. Buzz, buzz.

Contact our Editorial Team

Christina Janssen

Science Editor

University Communications

Tel.: +49.6151.533-60112

Email: christina.janssen@h-da.de

Translation: Sharon Oranski

Photography: Markus Schmidt