Car Hacking

If you can’t find your son or your daughter at some point, go and look in the garage. Because if word gets round about what two young scientists at Darmstadt University of Applied Sciences are getting up to with the electric cars used for research purposes at h_da, carport or whatever could quickly become his favourite place to hang out. With their specialist know-how and sophisticated technology, Timm Lauser and Jannis Hamborg, two PhD students of computer science at h_da, have converted a VW and a Tesla into giant toys for racing games. What’s particularly fun is the real driving experience with accelerator and brake pedal. Their invention has already earned them an invitation to Las Vegas: they presented their “Vehicle-to-Game (V2G)” project at the DEF CON Hacking Conference in August and at the same time supplied the instructions and software needed to reproduce it.

By Christina Janssen, 12.9.2024

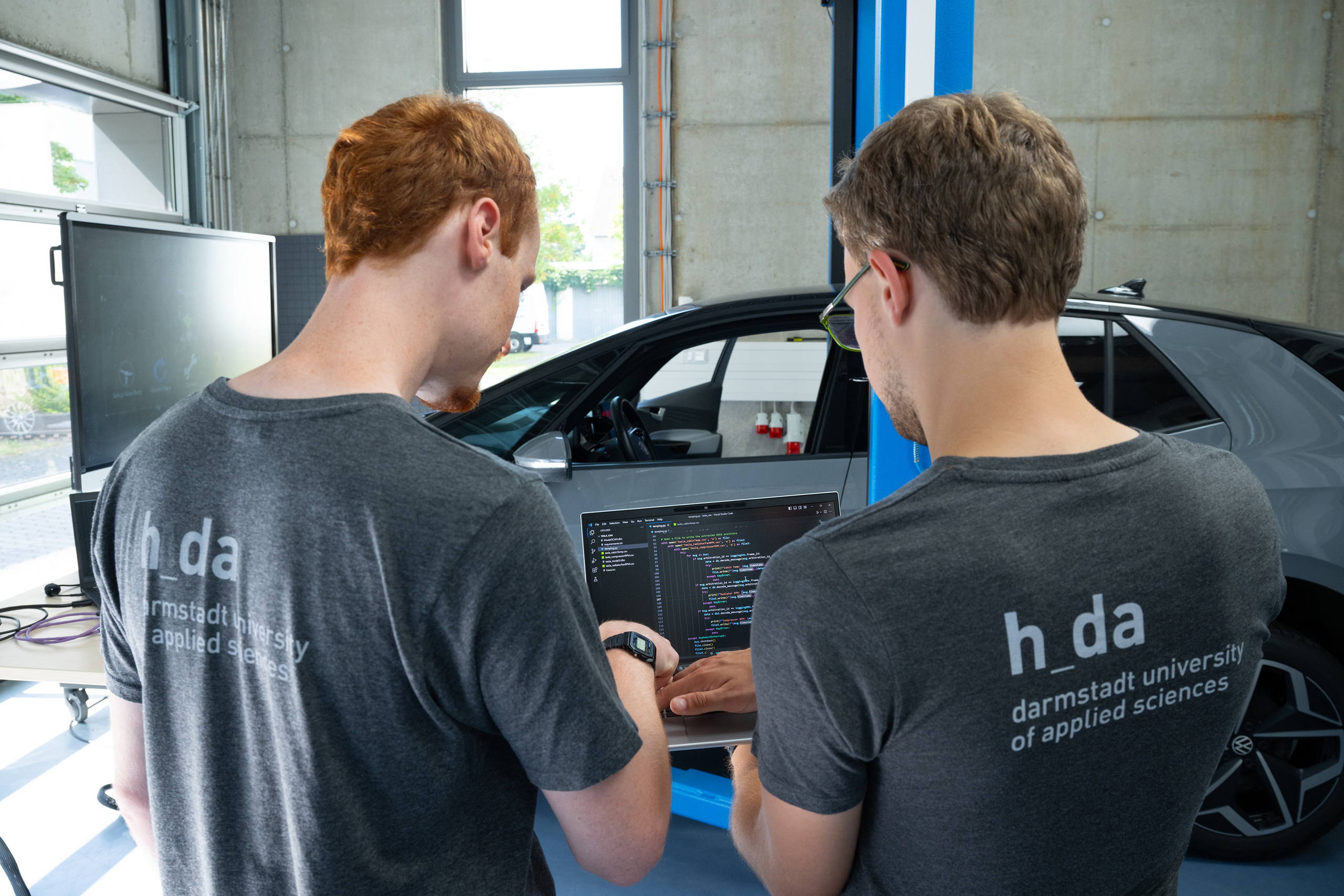

In their research, Jannis Hamborg and Timm Lauser are studying power exchange between electric vehicles and charging stations, among other things. Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G) is the technical term for this technology. But for a fun project that is meanwhile attracting international attention, the two computer scientists adopted and adjusted the abbreviation: “Vehicle-to-Grid” became “Vehicle-to-Game”. And that is why doctoral candidate Timm Lauser is taking on the role of a racing driver in the E-Mobility Workshop at h_da on a sunny Thursday morning in September. Highly concentrated, he sits in the driver’s seat of a VW ID.3 and stares at a huge screen that he and his colleague Jannis Hamborg have rolled up in front of the windscreen. On it, a yellow racing car whizzes past obstacles on narrow roads, collecting items and nitro, then Lauser accelerates again and switches to nitro mode by flashing the headlights. A fast-paced game – and much better than on the computer: after all, here you are sitting in a real car and controlling it with the steering wheel, accelerator and brake pedal.

“Understand how the car speaks”

“Are you serious?” might be the immediate interjection. But that becomes unwarranted as soon as the scientists explain how they came up with the idea: “The project is a ‘waste product’ of our research,” says computer scientist Professor Christoph Krauß. “In the Applied Cyber Security Darmstadt (ACSD) research group, we also deal with IT security in cars. We analyse vulnerabilities that allow hackers to manipulate the steering or brakes remotely, for example.” The point here is that to prevent such hacker attacks, you must first become a hacker yourself – like Lauser and Hamborg in their “V2G” project.

Step 1: Understand how the car “speaks”. To do this, the PhD students tapped into the electric car’s signal control to read and understand the relevant data: that is why the boot is packed with measuring equipment that can access the car’s wiring and signal transmission. In this way, the researchers were able to analyse exactly which steering signal leads to which vehicle movement or how the car’s braking operations are coded. And the vulnerabilities that expose them to interference. “The vehicle coding is slightly different for each manufacturer and model,” explains Krauß. “That makes this aspect of the project very complex and is the reason why it is part of our security research.”

In the second step, Hamborg and Lauser wrote their own software on the basis of the data obtained, which they can use to “hijack”, as it were, the vehicle’s signal control. “Our software translates the data we have read into our own defined format,” explains Jannis Hamborg: “In the game, the car gives nitro when I flash the headlights, and when I indicate, I can drop items, such as a red shell in a game like Mario Kart.” The V2G team then installed this software – Step 3 – on a simple minicomputer, a Raspberry Pi, which you can buy in any shop that sells technical equipment. Via an adapter they built themselves, the researchers can connect the minicomputer to the car’s on-board computer via its diagnostic interface, the instrument used to detect faults when a car goes to the garage for repairs. The V2G software then takes control: the Raspberry Pi masquerades as the game controller, sends signals from the car to a laptop via Bluetooth. Let the game begin!

Successful trip to Las Vegas

For maximum fun, the only thing that is then still missing is a large flat screen in front of the car. A laptop or automotive display will otherwise have to suffice. “It’s simply a cool application,” thinks Timm Lauser, “and a conversation starter. It also amazes people who are not so deeply immersed in the subject.” A project like this is a great source of motivation for students wanting to gain an insight into automotive security, he says. “All students like playing games – at least that’s the case in computer science,” adds Christoph Krauß, who, despite his many research achievements, exudes so little of the proverbial “grey eminence” that you are obliged to believe him immediately.

The fun-loving guys from the Department of Computer Science have already tested their creative idea with two of h_da’s own electric cars – a VW ID.3 and a Tesla Model 3. “In principle, it works – with certain modifications – for every manufacturer and model,” Jannis Hamborg is pleased to say. Luckily, anyone who wants to try it out for themselves can forego Step 1 and – depending on the manufacturer and vehicle model – Step 2, which require a high degree of scientific and technical understanding. All you need is a laptop, an OBD adapter for the car’s diagnostic interface, a suitable cable, the V2G software that the team has published on the GitHub platform – and, of course, you must love tinkering about. The estimated cost is under €50. The V2G team is happy for people to contact them and to make the data available if enthusiasts want to analyse their own cars and adapt V2G accordingly.

The professional community found the presentation by the IT specialists from Darmstadt at the DEF CON conference in Las Vegas, one of the largest annual hacker conventions worldwide with tens of thousands of attendees, truly fascinating. “It was a fantastic event,” reports Jannis Hamborg. “Nothing but technology enthusiasts interested in our project. We received a lot of input and new ideas. One colleague immediately wanted to know whether he could transfer V2G to aircraft. This is fundamentally possible, but far more complex.” Being invited to DEF CON in the first place, whose origins can allegedly be traced back to a legendary tech party, is an honour: everyone wants to be part of it, and the selection process is competitive. “Standing on stage there in front of a few hundred people is really something special,” says Lauser, summing up.

Contribution to more IT security

Like for the global hacker community that meets every year in Las Vegas, IT security is also a priority for the research group led by h_da professors Christoph Krauß and Alexander Wiesmaier. “If we discover security gaps when reading and analysing vehicle data, we report them directly to the car manufacturers,” reports Krauß. The scientists then give them sufficient time to rectify vulnerabilities before publishing their work. “This is how we cooperate with VW, for example, with whom we have a very trusting relationship,” explains Krauß, who is also working on IT security in vehicles within a large-scale project funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG).

Incidentally, a potential target for hackers to attack is not only the diagnostic interface described above, to which they would need physical access, but also the roof antenna. “Such attacks have indeed already occurred and made the sector sit up and take note,” says Krauß. “One example was the Jeep hacked in 2015.” Back then, two hackers took control of a Jeep Cherokee travelling at full speed via a vulnerability in the infotainment system. It was the first successful remote attack on a car to become known. “How to prevent something like that is precisely what Jannis and Timm are investigating.”

The two doctoral candidates have invested a lot of their free time in the V2G project – alongside working on their actual dissertations. “The project was purely a hobby,” says Jannis Hamborg. “It’s also fun for our students, who get to play at team events and our ‘HackCarDays’.” Following the project’s publication, several people expressed an interest in it and have already contacted the team with more in mind than just a gaming application. “We’ve received an enquiry from a company in Austria, for example, that would like to use V2G for simulation and training purposes,” they report. “Driving schools could use it for learner drivers’ first lessons, which would also be an interesting application.”

Anyone whose curiosity is now awakened can meet the V2G team on 27 September at the OpenRheinMain conference on the campus of Darmstadt University of Applied Sciences. By the way, the hacked VW will be jacked up on a ramp to ensure that there are only virtual collisions at most and that it does not accidentally crash through the glass doors of the E-Mobility Workshop - a little piece of advice for all those planning to copy the idea at home...

Contact

Christina Janssen

Science Editor

University Communication

Tel.: +49.6151.533-60112

Email: christina.janssen@h-da.de

Translation: Sharon Oranski

Photography: Markus Schmidt

Links

Computer science study programmes at h_da

Articles on the same topic

Heise, 13.8.24: Real cars turned into racing simulators

impact, 5.1.2023: Enhancing Cyber Security – A Game of Cat and Mouse

Golem, 13.8.2024 (in German): Raspberry Pi macht Auto zum Game-Controller

Heise, 2.7.2015 (in German): Hacker steuern Jeep Cherokee fern