Climate Resilient Urban Water Management

How can cities adapt to global warming with smart greening and water use strategies? This is the question that Jochen Hack, Professor for Climate-Resilient Urban Water Management at h_da’s Faculty of Civil and Environmental Engineering, is exploring. His work centres on a “blue-green infrastructure”, which he is co-planning and researching in the framework of practical projects in residential complexes or whole cities. Teaching and doctoral training are also close to his heart, where he can build on his long-standing contacts with Latin America.

By Alexandra Welsch, 22.4.2025

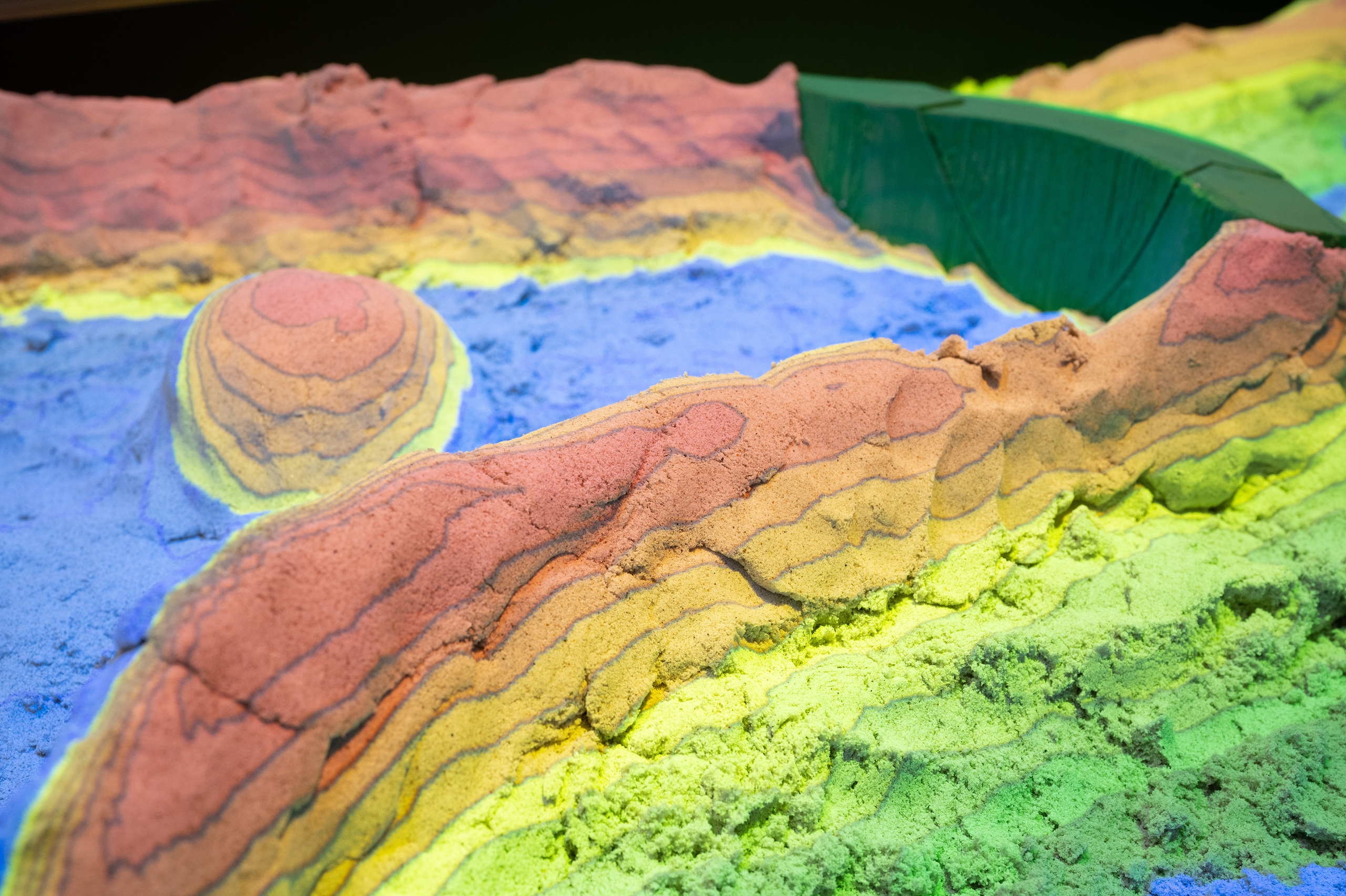

The Hydraulic Engineering Hall is flooded with the sound of rushing water. It comes from a waterfall in the concrete channel, 25 metres in length, along which water swirls and researchers observe sediment movement as the current flows in varying strengths. Meanwhile, at the other end of the hall, Jochen Hack is demonstrating a more “digital” type of water observation. He stretches out a hand and waves it slowly through the air over a sandbox. Between his fingers, something blue trickles onto the model landscape below. Hack grins: “That’s how you can make rain.”

The “Augmented Reality Sandbox” is a recent addition to the Hydraulic Engineering Laboratory at h_da’s Faculty of Civil and Environmental Engineering. The box can be used to model any type of landscape from sand. Positioned above it is a camera with a depth sensor that takes pictures of the landscape and recognises different heights and depths in the terrain, onto which a projector beams colours programmed by the topography software connected to the box. The sandbox was purchased on the initiative of Jochen Hack, who is himself also a recent addition to the faculty. The new acquisition is representative of the many approaches that Professor Hack has brought with him to h_da. As an expert in climate-resilient urban water management, he works a lot with digital landscape and numerical simulation models, and the sandbox forms a bridge between virtuality and haptics: “For me, it’s a way to help others access the digital world of geoinformation and modelling more easily,” says Hack. You can make very haptic models with sand, he says, and in this way create scenarios for the development of climate-resilient urban districts, for example.

Working with young people to create impact for society

You notice immediately that he is keen to present concepts clearly and vividly. Jochen Hack was previously Professor of Digital Environmental Planning at Leibniz University Hannover, and he is very pleased that in Darmstadt he will now focus more on teaching: “I’ve always enjoyed teaching, especially when it is interdisciplinary and project-based,” says Jochen Hack. “It enables you to work creatively with young people and has an impact on society.”

In Hack’s opinion, universities of applied sciences meanwhile offer good conditions “not only as far as research is concerned but also for doctoral training.” He would like not only to play an active role at h_da’s Doctoral Centre Sustainability Sciences but also to build more on his long-standing contacts with Latin America again. Among his other activities, he supervised an exchange programme with partner universities in Nicaragua and Costa Rica for six years and implemented projects such as the transdisciplinary junior research group “SEE-URBAN-WATER”, as well as teaching and researching nature-based solutions for sustainable urban development. Fittingly, the anniversary of h_da’s partnership with the Universidad Nacional de Asunción in Paraguay is coming up in September, and Hack would like to join the delegation. “The idea is to recruit doctoral candidates via subject-based collaborations and to focus on new projects.”

Climate adaptation between heavy rainfall and heat

In parallel, he wants to advance his own research. “The big issue is climate adaptation in cities,” he explains. As his work centres on water, he is looking at adaptation scenarios at the point of conflict between heavy rainfall events and heat, without neglecting quality of life and biodiversity. The catchword here is “multifunctionality”. “Networked greening strategies play a key role.” He explains that as an engineer he focuses on designing the necessary infrastructure, which he calls “blue-green infrastructure”. Hack recently co-developed an example of such infrastructure in a research project in Mannheim.

To illustrate this, he presents drawings of a new residential complex in Aubuckel, a suburb of Mannheim, with several blocks of flats positioned in a horseshoe shape around a large green area and three ponds. “How to make good use of wastewater and rainwater and create added value,” says Hack, outlining the task. On the one hand, this starts with the buildings: greywater is treated in a membrane filter system in the basement and reused for flushing toilets, washing machines and irrigation. “This means we use much less drinking water.” Outside, the ponds, dry wells and the many green spaces help to retain rainwater, even during heavy rainfall, that cools the microclimate. Hack and his team used numerical models of the microclimate and the urban drainage system to simulate the expected impact. Compared to the status quo, the model calculations showed a cooling effect of up to 25 degrees Celsius perceived temperature and a runoff reduction of over 30 percent in the sewer system below. “The project is a very good example of resource-efficient, climate-resilient construction,” concludes Hack.

More efficient irrigation of urban trees with the help of AI

The next practice-oriented research project will start in June. The title is “BlueGreenCity-AI – Development of an AI tool for the maintenance, monitoring and irrigation planning of urban green infrastructure using alternative water resources”. The Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Nuclear Safety and Consumer Protection (BMUV) has awarded €2m in funding for the project. Hack’s role is to develop an AI application and a web-based geoinformation platform. More precisely, it is about urban trees and arming them better against heat stress through more efficient irrigation, as well as ensuring that ecosystem services remain constant over the long term. “Today, irrigation tends to be ad hoc, without any monitoring or taking actual water requirements into consideration,” explains Hack. He is working on the project in close cooperation with the local parks department and his colleagues at Leibniz University Hannover.

“We are endeavouring to assess drought risk by means of various environmental parameters.” Among other methods, this is done with the help of sensors that measure soil moisture around the trees’ roots. “This generates a lot of data.” From weather stations and tree inventories, too. “The AI helps to structure and evaluate it.” With programming codes and algorithms, Professor Hack draws the data together on his computer and uses it to train AI-supported software. The aim is for the system to indicate which trees need how much water and to plan, by means of integrated route planning, the most resource-efficient and carbon-friendly routes. “The idea is to develop an adaptive system that also profits from on-site observations by tree experts.” Data would be recorded on a permanent basis and used to train the system further, he says. If it works, it could also become a useful tool for other cities.

That would be important to Jochen Hack not only as a scientist but also as a global citizen. “I’ve always been very interested in the natural environment,” he says, explaining his guiding principle. Humans intervene a lot in ecosystems, especially through built infrastructure. “How we can do this in a more sustainable way has always been my motivation.

Contact our Editorial Team

Christina Janssen

Science Editor

University Communications

Tel.: +49.6151.533-60112

Email: christina.janssen@h-da.de

Translation: Sharon Oranski

Photography: Jens Steingässer

Studying at the Faculty of Civil and Environmental Engineering

Information for prospective students (in German)