Who let the dogs out?

Care-dependent people ought to be able to live in their own homes for as long as possible. It is here that the BIM-4-CARE research project at h_da’s Faculty of Electrical Engineering and Information Technology aims to make a contribution: using artificial intelligence, the researchers want to close a gap between the professional implementation of homecare and the planning of any necessary home conversions. Among other things, they are also using a robot dog for this, which is fitted with a laser device to scan the person’s home.

By Alexandra Welsch, 14.6.2024

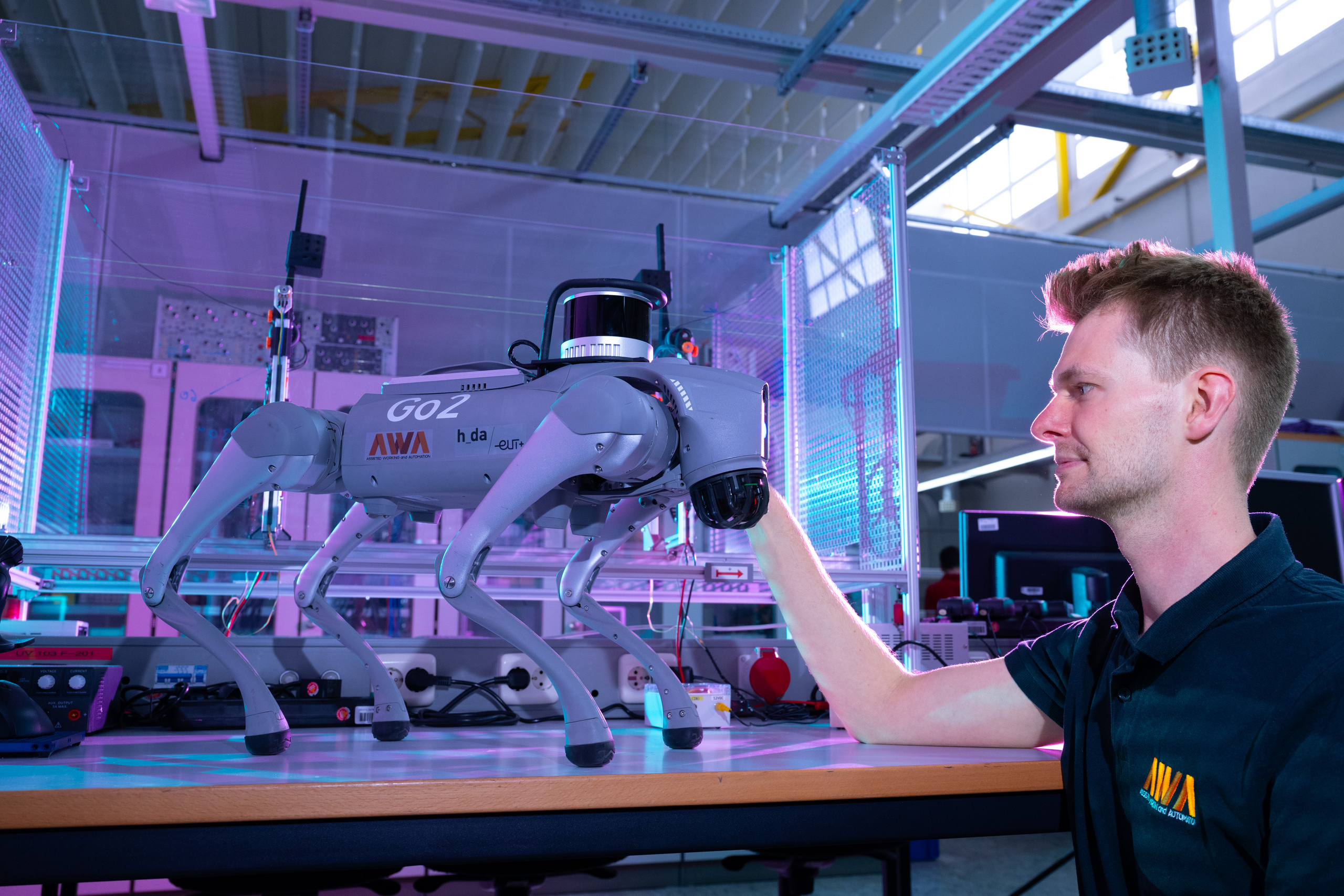

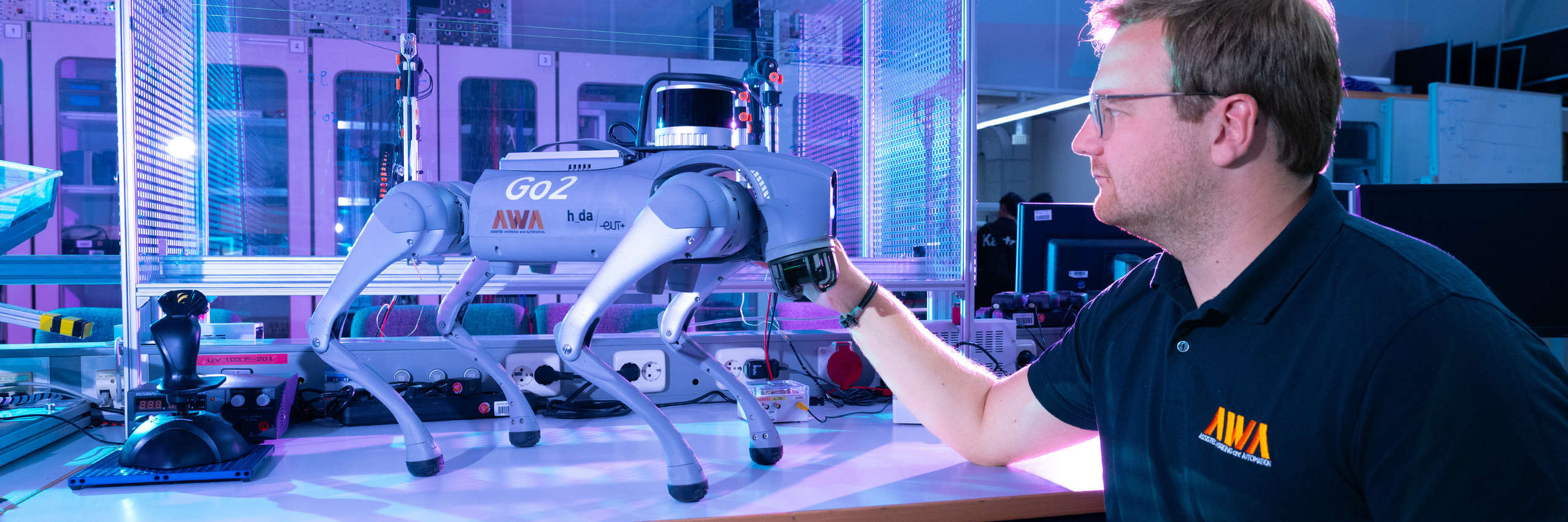

It has neither ears nor paws, it can neither wag its tail nor bark. Its body is not furry, but instead made of grey plastic and aluminium. But when the robot dog moves, it is strikingly reminiscent of its animal archetype: it darts off, comes to an abrupt halt, circles on the spot, stops, squats, stays crouched down for a moment, then suddenly leaps forward, sits up and begs. One particular skill, however, is less conspicuous at first: two sensors are installed on its back and on the tip of its snout that scan its surroundings with a laser.

The Faculty of Electrical Engineering and Information Technology (EIT) at Darmstadt University of Applied Sciences came up with the idea of the robot dog as part of the BIM-4-CARE project. Its official title is “Study and development of AI-driven algorithms for the evaluation of the physical and mental abilities of care-dependent persons to derive individual care assistance measures, under consideration of modern building automation technologies”. The research project, for which the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action (BMWK) has awarded funds of around €1.4m, will run for 30 months until the summer of 2026 and is intended to help improve care for people who need it.

80 percent of persons requiring care are looked after at home

“It’s about enabling people who require care to stay in their own homes for as long as possible,” says project manager Professor Sven Rogalski from the Faculty of Electrical Engineering and Information Technology, explaining the approach. The background is the growing number of care-dependent people in the wake of demographic change. In 2019, 4.1 million people already needed care, with around 80 percent of them looked after at home. BIM-4-CARE aims to help close an existing gap in the coordination between the professional implementation of homecare and the planning of home conversions – by planning and implementing patient care and building requirements and directly interlinking them using AI instead of alongside each other or even one after the other. For example, if a carer spots that a patient has advanced hip arthrosis, the software automatically suggests the installation of a walk-in shower and, on the basis of the structural dimensions already measured, a company can then plan this work without making a special visit.

“The project aggregates many different areas of expertise,” says Rogalski. In addition to a team of three people from his AWA research group at h_da (Assisted Working and Automation), four project partners from practice are also involved: Bruderhaus Diakonie and Pricura, two homecare providers, the architecture firm Leinhäupl und Neuber, and Open Experience GmbH as software developers. The whole project is embedded in the new AI platform “ForeSightNEXT”, part of the programme “Development of Digital Technologies” of the Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action. The aim is to provide smart living services via suitable AI methods on which projects can build their own data rooms and applications. “This is precisely where BIM-4-CARE comes in, as it addresses the field of application ‘Digital Health’, in particular homecare, in accordance with the call for proposals.”

“Idea born out of previous personal experience”

“We came up with the idea based on the previous personal experience of one of our project partners,” says Professor Rogalski. Their father’s home required modifications because of his care needs. Several people came to the house for the assessment and planning alone, from builders to insurance brokers. “That is stressful for the person affected and their relatives.” That is why this process should be made more efficient through the use of automated data collection systems – with the help of the robot dog, for example.

A low, continuous whirring sound emanates through the lab from the robot dog’s snout, where a kind of muzzle rotates. Behind it is a lidar sensor that uses laser technology to record objects in close range. A second laser sensor is located on the plastic quadruped’s shoulders that scans the whole room. “Robot dogs have the nice advantage that they have legs and can easily negotiate uneven surfaces and stairs,” says Till Weist, Master’s student in industrial engineering and research assistant. At this early stage of the project, he is still using a console to control the robot dog.

But that is not the ultimate goal. “We still need to give it the intelligence it needs to walk through rooms by itself, find its way and detect objects,” says Professor Rogalski, describing the further development work. Here, the “extension board” plays an important role; it is embedded in the middle of the robot dog’s back like a rucksack and is removable. “This is the actual ‘brain’ on which we are basing our research.” The data from the two lasers converge in this computing unit and are processed there using AI algorithms to generate true-to-scale, three-dimensional spatial images. Sven Rogalski calls this the “digital twin of the home”.

Robo in action...

Data from homecare provider and architecture office

Not only the robot dog supplies the researchers with spatial data. The architecture firm participating in the project advises them, for example, on building regulations for conversions to disabled persons’ homes. And the homecare providers deliver data on illnesses and constraints gathered from interviews with people requiring care. “We then receive data containers,” explains Till Weist. The team uses existing open source software to put them together. And reprograms it by changing individual parameters so that it corresponds to the intended use. “We then keep trying it out on the robot dog.”

The aim is for it to walk through the home of a care-dependent person by itself and record all the structural elements while a caregiver conducts an interview to determine the person’s needs. This would make it possible to document all the various aspects in just one visit. Once the data have been entered into a software programme, the system automatically plans what home modifications are necessary, tailored to the needs of the person concerned. “We are developing a system that records the spatial dimensions, aligns them with the clinical picture, and suggests modifications,” says Sven Rogalski, summing up. “You can continue to build on this plan even years later.” For example, if a person has multiple sclerosis and is likely to require additional aids as the disease progresses, such as handrails.

People are anxious of robots

However, although the sole aim of the research project is to improve things for people in need of care, the team has also encountered some scepticism. “People have reservations about acting as pilot users,” Professor Rogalski has observed. Older people are obviously less bothered about workmen or carers walking around their homes than a robot dog, he says. This is associated with anxieties – cue the transparent citizen. “We didn’t expect that.” And it makes the search for protagonists and homes to visit more difficult, he adds.

But the project has only just begun, and they are still optimistic. The team is currently developing methods for autonomous navigation and for recording spatial dimensions, the homecare providers are conducting interviews in parallel, and the first home inspections will soon start. And if they venture a look ahead to the end of the research project in the summer of 2026, they are convinced that everyone will have benefited. “That we will have made a contribution to the digitalisation of homecare and developed a system that makes it easier,” says Sven Rogalski. “And that the whole process – from applying for home conversions to their actual implementation – is shorter and simpler,” adds his colleague Tim Weist. “And that we can dispel old people’s anxieties and enable them to stay in their homes for longer.”

Contact

Christina Janssen

Science Editor

University Communication

Tel.: +49.6151.533-60112

Email: christina.janssen@h-da.de

Translation: Sharon Oranski